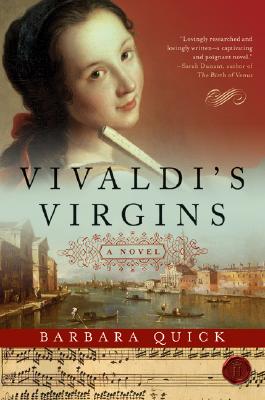

[Barbara Quick, author of Vivaldi's Virgins, takes us along with her on a journey of historical research for her latest novel, A Golden Web. Barbara will be teaching a class at Book Passage entitled Writing Historical Fiction coming up on April 30, 2011. Read more about the class at this link. You may listen to an audio podcast with Barbara about her research at this link.]

|

| Barbara Quick |

Everything that ever happened, and everything that ever will happen, is swirling inside and outside our brains at any given time. Most of the time, we only see and feel the time that makes sense in the context of what we know to be our individual lives.

But sometimes, some part of us—charged with a special receptivity—strays into the primordial soup where all time exists at once. And there, in that darkness—in the rush and swirl of infinity—I was tapped on the shoulder in 2008 by a young girl who looked straight into my eyes and whispered, “Tell my story!”

She was a brilliant young medical student who studied and died in the early 14th century in one of Europe’s oldest centers of higher learning, the University of Bologna. I had found the barest outlines of her life in somewhat of an accidental search on Google. I was looking for information about another female anatomist from Bologna, far better known, from the 18th century.

I had sat down at my computer, dressed in my workout clothes, at 10:30 in the morning. When I looked up again, it was dark outside, and I’d written a fully fleshed-out book proposal. I knew the girl’s father and mother and the struggle they’d put up against their daughter’s determination to leave home and study medicine. I knew her good-natured jock of a big brother who was more than happy to have her sit by quietly while his tutors lectured him, so that she could provide all the answers for him, discreetly whispered, when he took his exams. By way of a thank-you, he took her out riding with him, taught her to hunt and dress the game they bagged together.

I knew her little sister who was poised to get married and yet couldn’t until Alessandra stopped being so stubborn and started behaving like a proper girl. And, clearest of all, I heard the voice of the young man who loved her, chosen by her parents and yet making them promise to keep the betrothal secret, so that he could win Alessandra’s love on his own.

I saw her death at the age of nineteen. I saw her fevered eyes that glittered not only with the disease contracted from one of the corpses she used in her medical experiments, but also with the knowledge that—magically, against all odds—she’d accomplished what she’d set out to do.

|

| A Golden Web |

I took heart when I woke up in my hotel room, with the doors flung open over the garden, to hear a joyous chorus of birds. They were probably singing the same songs, I reasoned, that Alessandra had heard on her own first morning in Bologna. Time, for some aspects of the world, at least, changes very slowly.

In the ornately frescoed, vaulted rooms of the Sala Borsa, one of Bologna’s gorgeous public libraries, I found sources I never would have been able to find at home—and I knew I had made the right decision in coming. Illustrated manuals of the time clearly showed a girl in boy’s clothing assisting at the anatomy lessons of Alessandra’s mentor, Mondino de’ Liuzzi. In my original story outline, I’d had Alessandra’s parents insist that she dress as a boy for the insane adventure they only consented to finally because she threatened to kill herself if they refused. They insisted as well that she travel in the company of her nanny—which did much to compromise the public image Alessandra hoped to project as a brave young cavalier.

I was in a trattoria, eating my supper and parsing out one of the articles in Italian I’d photocopied at the library, when both facts were confirmed: Alessandra is reputed to have dressed as a boy during her time at school, and she traveled in the company of her bambinaia. I shed a couple of astonished tears over my tortellini.

Everyday I walked something like six hours over the cobble-stoned streets and alleys of Bologna—which is arranged like the spokes of a wheel radiating out from Piazza Maggiore, reigned over by a huge statue of Neptune and his entourage of nymphs whose breasts burst forth with fountains of water. I sought out the places where the medical students were reputed to hang out in the 1300s, looking for the sanctuaries that Alessandra might have turned to in moments of fear or despair. I climbed the 498 precipitous steps of the Torre degli Asinelli to imagine the landscape as it must have been during Alessandra’s time, mentally covering over buildings from the 15th century onwards and blotting out any signs of the Renaissance, the Baroque, and modern times. When my feet were covered in blisters, I borrowed a bicycle from the hotel and zipped with utter joy and abandon from one church, library, archive, or hallowed spot to the next, playing chicken with buses and scooters and cars. I felt safe: I felt—as frightening as it is to admit—invincible.

I walked up the pilgrimage road, now sheltered by two kilometers of porticoes but merely a path in Alessandra’s time, to the 18th century church of San Luca, poised thirty meters above the town, which started out as a convent founded by a solitary, visionary nun. I imagined Alessandra’s bereaved best friend and fiancé, making the pilgrimage up to the sanctuary barefoot, praying to be reunited with his beloved in the next life. On the way down, I strayed off the pilgrimage road to follow a grass-covered pathway into the countryside, taking in the trees and wildflowers in the same way I had taken in the birdsong. A flurry of white plum blossoms blew down on my path and I could hear with precision the voice of Otto, Alessandra’s fiancé.

I have no doubt that my passion and enthusiasm for my subject was infectious. Everywhere I went, doors opened for me.

|

| Vivaldi's Virgins |

I never thought that history would become my life’s passion. I never even liked history when I was at school, apart from the context of literature, music, and art. But history has suddenly been revealed to me as the place where I live, where we all live, side by invisible side with others who—if we get quiet enough and listen carefully enough—will touch us and tell us their stories.

—Barbara Quick

Northern California novelist Barbara Quick is the author of Vivaldi’s Virgins (which has been translated into 14 languages) and A Golden Web, published last year by HarperCollins.

1 comment:

Barbara, Wonderful post. I enjoyed reading it. I especially loved the sentence "But history has suddenly been revealed to me as the place where I live...." Perhaps time travel will someday be revealed as only a matter of will. Thomas

Post a Comment