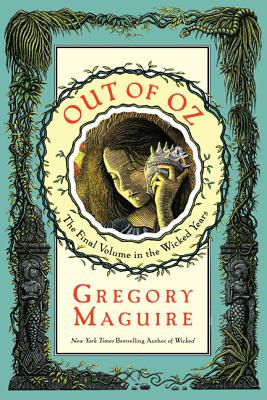

| Author Gregory Maguire |

Gregory Maguire: When I reached the end of volume two, Son of a Witch, I

thought the two first volumes sat together on the shelf very handsomely. Like,

say, Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, or the original publications about those

March girls, Little Women and Good Wives (which eventually were published

together as the Little Women we know so well today). But it is true that, in

order to lend the fantasy novels in Oz a great sense of verisimilitude—of

grittiness, of sordor as well as glamour—I had left a lot of plot strands

dangling. Face it, that is how most of our lives are lived, with less than

adequate knowledge about how our friends and enemies, our children and our

parents, actually lived before we came along or will live after we die. This

meant that the starting material, the yeast as it were of the final two books,

were entirely in place when it came time to draft A Lion Among Men and Out of Oz.

Zack Ruskin :The final installment in the Wicked Years is titled Out of Oz. Is there intent on your end to expand the world of the series, or does the

“out” refer more to the book’s place as a closing chapter?

Gregory Maguire: I don’t want to give anything away, but I will say that Out of Oz is a title that has many different overtones. For one thing, it hearkens

back to an archaic way of talking about the news from a dark and distant land:

“What’s the news out of Africa ? What’s the

news out of Indochina ?” “What’s the news out

of the dugout, the PTA High Command,” etc. It also, of course, implies the

world beyond Oz, and that world involves a girl we have met before, named

Dorothy. Since Dorothy would make a return visit to Oz, she would have to come

there from “out of Oz,” and that is how the novel opens. Finally, or nearly

finally, I was happy in coming up on that phrase because all the original Oz

novels ended in “of Oz.” Think about it. The Wizard of Oz. The Marvelous Land of Oz. Dorthy and the Wizard of Oz. The Emerald City of Oz. So I liked that affinity, too, of phrases.

Zack Ruskin :From a technical standpoint, with a 519 page book like Out of Oz, when do you know you’ve finished? Does the page count simply reflect how

long it took you to tell the final story, or did you want the last book to have

a more substantial impact?

Gregory Maguire: I began the book knowing what the last scene was going to be

like—indeed, I wrote a version of the last few pages about 15 years ago, when I

drafted an aborted sequel to Wicked called The Education of Tin and Straw. But

it is true that much of the novel had to be written in order for me to

understand what it was about. There are a lot of characters to give tender

mercies to, and a lot of mysteries to resolve, and I was resolved not to rush

it, or it would feel like rushing around the landscape of Oz with a Zamboni,

smoothing out bumps without regard to which bumps needed to remain…

Zack Ruskin :What’s the bigger challenge: reducing your story to the few

words of a children’s book or filling the pages of an adult novel?

Gregory Maguire: I think that writing for children is much harder for the

reason you suggest. Indeed, I am not a proficient writer of short stories or

picture books, and while I love poetry I am not compressed, concise enough.

Look at how long my answers are to your questions! Still, the best of

children’s writing is strong, compact, revelatory. I think of books like Charlotte's Web and Tuck Everlasting, books that don’t have an extra sentence in them. Or stories slim

and strong as Horton Hears a Who, Where The Wild Things Are, or Millions of Cats. Those books work as deftly as poetry. I’m in awe of writers who can do

that. (M. B. Goffstein, picture book writer, is one who excels at it. Her

little books are like haiku.)

Zack Ruskin: What does Oz exemplify to you? What facets of the setting

afforded you the chance to set four novels there?

Gregory Maguire: I had always loved the countries of Narnia, Neverland, even

Wonderland. I came a bit later to Prydain and to Earthsea and Middle-earth, and

liked them too though they were less clear in my mind. What five of the six of

those countries mentioned above, however, have in common is their essential

Britishness. They were discovered and invented either by Englishmen or by an

American in homage to those same books. The one exception is Ursula Le Guin’s

Earthsea books, which is more like The Odyssey than anything else.

This is to say, the only truly American magical landscape is

Oz. When I thought about it (sixteen, eighteen, twenty years ago), I realized

that Oz had length and breadth and complexity, even in L. Frank Baum’s fairly

simple and comic tales, that matched the ladscape and cultural differences of

the different parts of our country. I began to see it was a metaphor large

enough for US. Narnia was too small, the Shire in the Tolkien books too

cozy-villagey for us. It would take a broad, disassociated landscape to deal

with what we have to deal with in this country, and Oz presented itself for my

use. Luckily, the copyright on Oz had just lapsed when I began…. (I say luckily

because I knew nothing of copyright law when I began. I just began.)

Zack Ruskin :When you’re working in a setting outside of reality, what

kind of parameters do you set to ensure readers never feel (unintentionally)

lost or confused?

Gregory Maguire: I am a great admirer of maps, and I have drawn all the maps

for my four books myself. (They are beautifully redrawn by Douglas Smith, but

every particular of them, including even how the borders are drawn, how the

mountains and streets and marshlands are indicated, are my design.) I also, in

the later two books, supply time lines, genealogies, and summaries of recent

history—a kind of “Our story so far” summary—for those who have been so moved

as to read other fiction in the years in between I supply them installments. Is

all this extra armature useful? It is hard to say. It is certainly useful to

me, because I don’t want to get things wrong. (And in the first two books I did

get a few things wrong, and had to bend over backwards to find a way to make

things right.)

Zack Ruskin: Some of your novels take a familiar folk tale or piece of

popular fiction as their inspiration, but with the Wicked Years, the territory

is more uncharted. As you approached your fourth book in the series, did you

still feel some kind of distant allegiance to L. Frank Baum and his vision?

Gregory Maguire: It is interesting to note that Baum wrote 14 novels about

Oz, and then after his death “sanctioned” authors wrote several dozen more. As

I grew up, only Baum’s first two novels were available in my public library. I

knew there were lots of other books out there, but I couldn’t find them. I

think in some ways their absence provided me with some of the urgency to find

out what Oz was like, and some of the license to my imagination to invent it.

When, a seasoned adult writer, I finally did begin to find copies and read

them, I was less than impressed. My own belief that Oz had a history the way

Narnia and Middle-earth did was rudely snapped when I did find the later books.

They unraveled in scarcely-recognizable chronological order, being more

interchangeable, like episodes in “The Simpsons” viewable in any which order.

So I felt Baum himself had, in a funny way, given me dispensation to be more

concrete about history, about how our actions shape the actions of people who

will come after us, by choosing not to do that himself. Finally, for those who

know the Baum books well, there are many sly tips of the hat to the inventions

of Baum in some of the minor characters in my novels.

Zack Ruskin: There’s a definite resurgence of folk tales being used as

source material. What qualities of the “fairy tale” lend itself so naturally to

being reinterpreted over and over again?

|

| Set of the original Oz books by L. Frank Baum |

Gregory Maguire: The traditional fairy tale is like a trunk that has been

handed down through the generations. The lock is smashed, the interior compartment

is missing, the name painted on the top is illegible, the braces have been

replaced three times and don’t match anything else. This is to say that the

very oldest tales very often betray, through missing bits and unmatched

symbols, both evidence of their age and also an invitation to the inventive

mind. I’ll give you an example. Why, in Cinderella, is her coach made from a

pumpkin? Why not a rutabaga, a bird’s nest, a scuttle of coal, a lemon meringue

pie? There is probably an answer—some storyteller in a North European farmstead

had a big pumpkin on the hearth that night, and the image held. But why, then,

glass slippers? Glass slippers have nothing to do with farming life. And they

have nothing to do with the story, I mean, that they are glass—except perhaps

that they are unique, one of a kind (so when the Prince brings out one slipper

and Cinderella its match, she proves in her grime and lowliness to be the

splendid woman he fell in love with.) But why not slippers made of

hummingbird’s wings? Of pumpkin rinds? The facts of those inconsistencies

between images, of the unexplained reasons for why things are as they are,

provide the handholds and the openings for a writer wanting to work with the

material. Then again, fairy tales come with their built-in audience. Much more

appealing to the reader browsing in the library or bookstore to pick up a book

telling secrets about Cinderella than to risk spending time and money on a

story about Pizzarina, the crusty daughter of the wizard’s pizza chef.

Zack Ruskin: Did the smash success of the Broadway adaptation of Wicked

have any bearing on your choice to revisit the Wicked saga? Have you a found a new audience of readers

from fans of the musical?

Gregory Maguire: In a word, yes. Wicked had sold three quarters of a million

copies before the play opened, and a few years later it had sold four times

that amount. (The Wicked Years sequence has sold 7.5 million copies worldwide

to date.) With the surge in readership came a surge in reader mail, and the

barrage of questions from readers who wanted to know more became a force I had

to deflect or drown under.

|

| Still from the Broadway musical adaption of Wicked |

Gregory Maguire: I am not sure. Any ideas? Maybe it is time for Pizzarina…

Zack Ruskin: Your stories tend to be rich in story, dark in subject

and wholly original. Are there certain elements or traits to your storytelling

that you make a conscious effort to include, or are the themes of your work

more organic in nature?

Gregory Maguire: I love fantasy novels. My favorite is T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, the retelling of the King Arthur cycle that inspired the

musical “Camelot.” What I loved best about that erudite work is that it was

poetic, comic, romantic, adventurous, magical, without ever losing sight of

being morally serious. Indeed, without that final component, I would never find

myself much interested in all the rest. So I try to make sure to pose a moral

question to myself in the writing of a novel, even if readers never notice, or

ever seem to be able to put their finger on what it is that is motivating them

to turn the pages. I believe the understanding that our choices have

consequences, even in worlds in which magic has some sway, is the signal most important

element to include in any novel.

Zack Ruskin: My new go-to question is to ask about the potential for

a series to be rendered as graphic novels. Do you see your Wicked Years books

as potential candidates for that medium?

Gregory Maguire: Interesting you should ask that—I have just begun to read

graphic novels myself. Just this past weekend I finally read Chris Ware’s

magnificent Jimmy Corrigan, and before that I read David Small’s Stitches,

Craig Thompson’s Blankets, and I’m deep inside the wonderful Wonderstruck by Brian

Selznick, which is part prose drama and part silent film on quickly turned

pages. So I will be tussling with your question quite a bit in the months to

come.

Zack Ruskin: You’ve stated before that the idea for Wicked came from

your desire to explore the idea of whether people are truly ever inherently

evil. Would say you’ve satisfied your curiosity on the subject?

Gregory Maguire: Do you mean have I come to a conclusion if people are ever

truly inherently evil? No. But I have concluded, anecdotally, that I believe

the roots of human demonstrations of evil—when they are individual and

specific, not cultural or institutional—lie deeply in something I would call

self-hatred. I believe that the biological imperative not to kill or main one’s

self runs so deeply (even if ultimately breachable) that self-disgust is then

turned outward, into contempt, into violence, into the dismissal of others as

less than human, and therefore less deserving of justice, mercy, and tolerance.

Zack Ruskin: What, if any, elements of the classic 1939 film "The Wizardof Oz" influenced your Wicked Years series?

Gregory Maguire: I knew the film before I knew the books—I think this story

is the only one in my childhood (except maybe "Peter Pan") of which this can be

said. Well, I didn’t see much TV or many films as a child. But the film is

still under copyright so I had to tread carefully, evoking my Oz through

inference rather than direct quote. (No one can sing “Over the Rainbow” in the

Wicked Years, though I can and did suggest that Elphaba sing a song of longing

that dissolved like a rainbow after a storm… ) I found Judy Garland’s slightly gluey, over-earnest depiction of Dorothy

both attractive and a little off, and it was amusing to build on that for my

depiction of Dorothy in Out of Oz rather than in the far more sober and

somewhat humorless stout little Dorothy in the original novel.

Zack Ruskin: When a reader finishes Out of Oz, what are you hoping

they’ve taken away from your series as a whole?

|

| Still from the 1939 classic "The Wizard of Oz" |

Gregory Maguire: I think I could make a statement about the series on a

whole, about its themes taken all together, like this: Most of us are not

stuffed with extraordinary looks, gifts, powers; yet the world we have to live

in requires extraordinary intervention. If we are not magically powerful, then

we must find other ways to use our lesser powers to the good of the world, for

if we do not, we are condemned to founder in darkness. Heroes and heroines

(like Harry Potter, like Elphaba Thropp) can give us courage, but us less

magnificent mortals must work together to make magic happen.

No comments:

Post a Comment