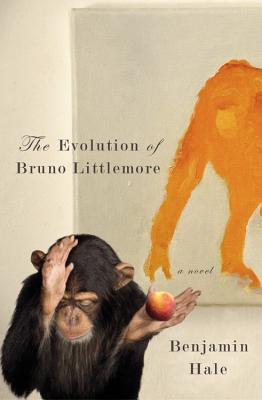

| Benjamin Hale |

|

| The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore ($25.99) |

Benjamin Hale: It was about four years, from one end to the other. The first fifty pages or so I wrote in about a week, then I wrote the last chapter, and then I spent the next three years writing them together. It took me about three years of pretty hard and concentrated work to get a finished draft, and then there was another year of cleaning it up some with my agent and editor.

DP: I understand that you have an MFA in fiction from Iowa Writers Workshop—did you begin Bruno while you were in the program? Did the workshop environment fast track the development of the book?

BH: I did start writing Bruno at the very end of my first semester at Iowa, yes. The main advantage by far of an MFA program—and particularly a really good one like Iowa—is the amount of time it gives one to write. Time is a writer’s most precious resource, by far. I only showed a little bit of it to a workshop, once, at the very beginning of my process of composition, and after that it was something I worked on just on my own, while putting it aside now and then to write short stories. But the workshop spurred Bruno on in other ways, as well. In one sense, Bruno is my personal, noisy little rebellion against everything that irritates me about what people call “workshop” fiction.

DP: Can you tell us about how you came up with the idea for the book? Did it stem from your interest in a particular subject like biology, sociology or linguistics, or perhaps from a fascination with chimpanzees?

BH: At the time I started writing the novel, it was my first semester at Iowa, and my girlfriend at the time was living in Chicago, which is a three-hour-ish drive from Iowa City, so I was in Chicago half the time. She was a grad student in architecture, which meant she was really busy, whereas I, an MFA student, had effectively nothing to do (I was supposed to be writing). So while I was waiting for her to finish her work, I would often spend the day in the Lincoln Park Zoo, watching the chimps at the primate house. Sometimes I would sit there and watch them for three, four hours... At the same time I was also getting really into Philip Roth and Saul Bellow (the unofficial novelist laureate of Chicago; the first line of The Adventures of Augie March is "I'm an American, Chicago-born—Chicago, that somber city..."; the book's Chicago setting is in part a bit of an homage to Bellow). Often I would read in the zoo, when the chimps weren't doing anything. There was one time when I was reading Portnoy's Complaint in the Lincoln Park Zoo Primate House, and I looked up at the poor chimps stuck in their claustrophobic enclosure during one of those brutal Chicago winters, and an idea was born.

Another germ of inspiration for the book was certainly my own lifelong fascination with chimps. I remember being profoundly affected by a moment in a Jane Goodall documentary that I saw as a kid. It was the story of Flint, who essentially had the chimp equivalent of an Oedipal complex. He had a neurotic, obsessive, unhealthy attachment to his mother, Flo. He was like the chimp Norman Bates. For instance, he clung to her back far beyond the time in childhood when chimps ordinarily quit doing that. When Flint was an adolescent, his mother died—simply because she was old—it happens. But he could not accept the death of his mother. He dragged her corpse around with him for weeks afterward, refusing to eat or sleep, and eventually wasted away himself. Jane Goodall found him, still holding his mother’s body, dead beside a creek. I was powerfully shaken, disturbed, haunted by this as a child. I was chilled by the idea that an animal, a chimpanzee, could be just as crazy as a human being.

DP: Did you do a lot of research for this book? What was that process like? Did you conduct the bulk of the research before you began writing, or did you do research as you went along? What types of materials were you looking at, scientific studies on animal behavior? Polemics on language?

BH: The most interesting research I did was at the Great Ape Trust, outside of Des Moines, Iowa, just a couple hours’ drive from Iowa City. The only ongoing ape language experiments in America happen there. Kanzi, the bonobo, is their most well-known ape. I attended the Decade of the Mind conference at the GAT—an annual symposium on the science of consciousness—and went back and visited the apes a few times after that. William Fields, the current director of the bonobo language research program, was particularly receptive and helpful with my research. I also revisited the chimps at the Lincoln Park Zoo whenever I was in Chicago, and on top of all that, I read piles of books—I probably fed at least two-hundred books into my research mill. Frans de Waal’s writing was particularly helpful to me, but I also read all kinds of other stuff: anthropology, primatology, philosophy of consciousness, philosophy of language, linguistics, semiotics.

DP: The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore is rich with cultural and literary references, and in my opinion there is a certain sense of joy and exuberance to your writing when you evoke them—one of my pleasures in reading the book was noticing your own pleasure in commenting, remarking, and extending these references. Was it your aim from the get-go to do this or did it emerge naturally as you wrote?

BH: I think it was probably something that emerged from Bruno’s voice. It’s a voice that allows for a lot of play, and I just let myself go. Ordinarily, if I’m writing fiction in the third person, there’s no way in hell I’d casually drop references to Ovid and things like that. That would be insufferably obnoxious. But Bruno is obnoxious. Because he’s such a bombastic, narcissistic, deeply insecure show-off, his voice allowed me to squirt as much frosting as I pleased on the cake.

DP: Many critics have commented on the skillful and complex voice you’ve created for Bruno as narrator. How did you arrive at Bruno’s voice? Was it one that you were immediately able to inhabit, or did it evolve over time through rewrites?

BH: Bruno’s voice emerged into its mature state fairly quickly. Bruno was a mask that was a hell of a lot of fun to put on. Initially it began as my own parody of the voice of Portnoy from Portnoy’s Complaint, but then there were myriad other influences that began to be interwoven into it: Oscar Matzerath from Gunter Grass’ The Tin Drum, Henderson from Henderson the Rain King—plus voices from the epic English bildungsroman novels I somewhat-consciously wanted Bruno to follow in the tradition of: Tristram Shandy, Tom Jones, David Copperfield, and so on. But I wanted there to always be a veil of irony between Bruno and me.

DP: Did you read while working on the book? If so, what books were you reading while you wrote Bruno? Did you find that they intentionally or unintentionally seeped into your own work?

BH: Yes, I’m always reading. I’ve talked about some of the main influences above—here’s an incomplete list of books that I remember reading while working on Bruno, all of which influenced it in some way: Steven Millhauser (all of his books, but Edwin Mullhouse was an especial influence), Roberto Bolano’s 2666 (resulting in some long-ass paragraphs in Bruno), Tristram Shandy, Tom Jones, David Copperfield … Saul Bellow: Henderson the Rain King (several times), The Adventures of Augie March, Herzog, Mr. Sammler’s Planet, Ravelstein … Philip Roth (I read almost all of them, I think, but I especially love Portnoy, My Life as a Man, Sabbath’s Theater, and The Human Stain), Mary Gaitskill’s short stories (genius). Let’s see… Jakob Wassermann’s novel about Caspar Hauser, Mikhail Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog and The Master and the Margarita. Lots of Saussure, some Wittgenstein. Martin Amis’ The Rachel Papers. I reread Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy books at one point. Paul Celan. Yeats. Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds. Lots of John Berryman. Celine’s Journey to the End of the Night. That’s still a very incomplete list, but it’s a start.

DP: Some writers tell us that the act of writing is sheer agony, while others tell us it’s fun. Do you fall on one side of the issue or the other?

BH: When it’s going well, I love it. For the most part I had an absolute blast writing Bruno. I knew I was having a good day writing if I found myself alone in my room with my manuscript, laughing.

DP: I understand that you are teaching fiction writing at Sarah Lawrence this spring. Was there anything significant that you learned through writing the book—not necessarily from your own MFA education—that you plan on sharing with your students?

BH: Too much to say!

DP: What are you working on next?

BH: Yep. I have a collection of stories sitting on deck for now, all done and ready to go. Meanwhile, I’m working on another novel. This one is much more realistic. It’s still in such a pupa stage of development that I don’t want to jinx myself by talking about it too much, but for now it’s about a friendship between a poet and a pot dealer. It might turn into my stoner comedy. It’s like Cheech & Chong & John Berryman.

***

No comments:

Post a Comment